The director of the Centre for Architectural Structures and Technology (C.A.S.T) and his students have been experimenting with a revolutionary technique using material similar to a "blue tarp found at Canadian Tire" to mould concrete into aesthetically-pleasing -- and useful -- new shapes for the construction of buildings.

"Because the fabric is flexible, you can form the concrete into a whole different class of geometries that would really be difficult to do with wood," he says.

Traditional methods of constructing concrete buildings with rounded shapes are expensive, complex and time-consuming, which is why many cement structures have flat surfaces and angular shapes.

"You'd need boat builders and have to pay them a ton of money to build curved wood forms, but fabric will follow the curve form naturally."

West and his students discovered a method to build large, one-piece geometric shapes that curve, ripple and bulge. They also found it to be more cost-effective and environmentally-friendly than conventional methods of pouring concrete.

"When you make a concrete building, you have to construct the whole building as a void out of some other material to make the mould to cast the concrete."

Wood, frequently the material of choice, is often discarded in the landfill after a handful of uses.

"In terms of construction waste, it's a horrible way to use wood, which can last hundreds of years if you treat it right."

In contrast, the geotextile fabric -- made from a flexible plastic called polypropylene -- used to make the forms in the C.A.S.T. lab is low-cost and reusable. West says his methods to create concrete structures require hundreds of times less material than traditional ways of forming concrete.

It also creates surprisingly sturdy concrete structures.

"It's counter-intuitive," admits West, who came up with the idea while working at his other vocation: artist. (The bulging, decorative columns at the front of the Manitoba Theatre for Young People at The Forks are examples of his artwork using concrete and fabric forms.)

It seems unlikely that what is essentially a tarp can be used to form a concrete column, beam or truss that will support a building, but the calculations do add up.

"The first time I did (the calculations) -- I'm not an engineer but I have a really good structures education -- the number was way too low."

He showed his math to an engineer and asked what he had been doing wrong. "He looked at them and said 'this can't be right.' "

But it was. Force naturally tends to follow curved paths, West says, and fabric moulds allow wet concrete to form into these natural curves. To hold it in place, the fabric forms a tension membrane, one of the most efficient known ways to resist force, until the concrete dries.

Rebar is also used, he says, in much the same way it is with traditional concrete construction methods.

Then the fabric is removed, leaving the curved, cement structure in place.

Using fabric forms in concrete construction, West says, is engineering imitating nature. In fact, many of the designs conceived in the C.A.S.T. lab look like they were made by Mother Nature herself.

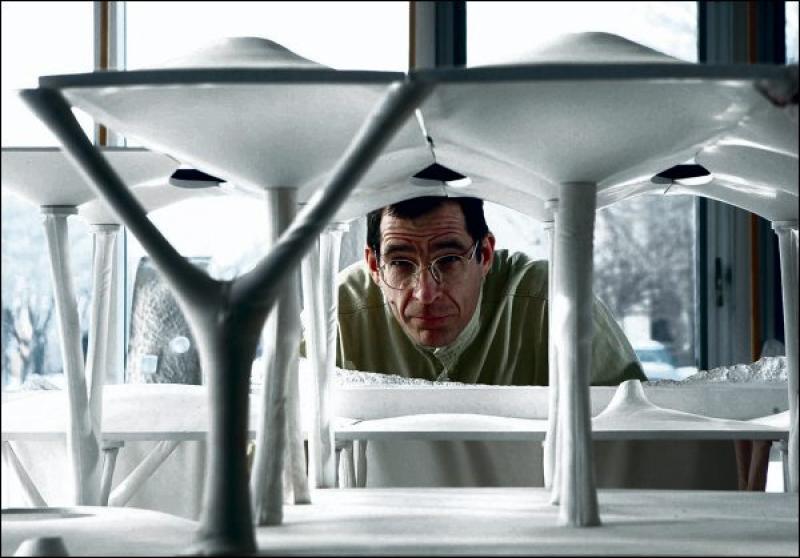

The lab has produced Y-shaped brace columns that look more like tree branches than concrete support structures.

At the Laforge concrete factory in the city, where C.A.S.T. has been able to build designs to full scale, the team has constructed concrete trusses that look more like bones than the steel trusses seen supporting the roofs of big box stores. Unlike the steel ones, which need to be coated with fire retardants, the concrete trusses are naturally fireproof, West says.

The C.A.S.T. lab has also constructed walls, which look like drapes frozen in concrete, by spraying cement on a hanging piece of geotextile fabric. He says engineers are still crunching the numbers to ensure the concrete curtain can function as a sturdy wall, but he is optimistic it will stand up to the test.

"There are things that we know how to make that are quite simple and straightforward, but because the geometries are more complex than flat planes, the engineers have to catch up to us."

Engineers have already proven that many of the designs -- like the Y-branch column -- are safe to use. It's now a matter of getting architects and the construction industry to on board.

The Manitoba-grown invention placed third in North America at the Swiss-based Holcim Awards for Sustainable Construction Application in 2005, and architects around the world do know about the process.

"The conversations (with architects) are short because I'll ask them, 'Do you have a builder, and do you have price?'" West explains, adding no builders can quote a price because they are unfamiliar with the construction method.

"If they sent their builders here, we could train them."

He remains confident, however, that fabric forms will be commonplace in construction some day because they make simple, eye-pleasing structures that, above all, are cost-efficient.

"Significant change in construction technology takes a very long time," says West, who has been developing the process for 18 years.

"It takes decades for a new idea to be accepted, but we're patient."