Cathy Clark

Try digging a plastic-lined trench around your potato crop to deter potato beetles.

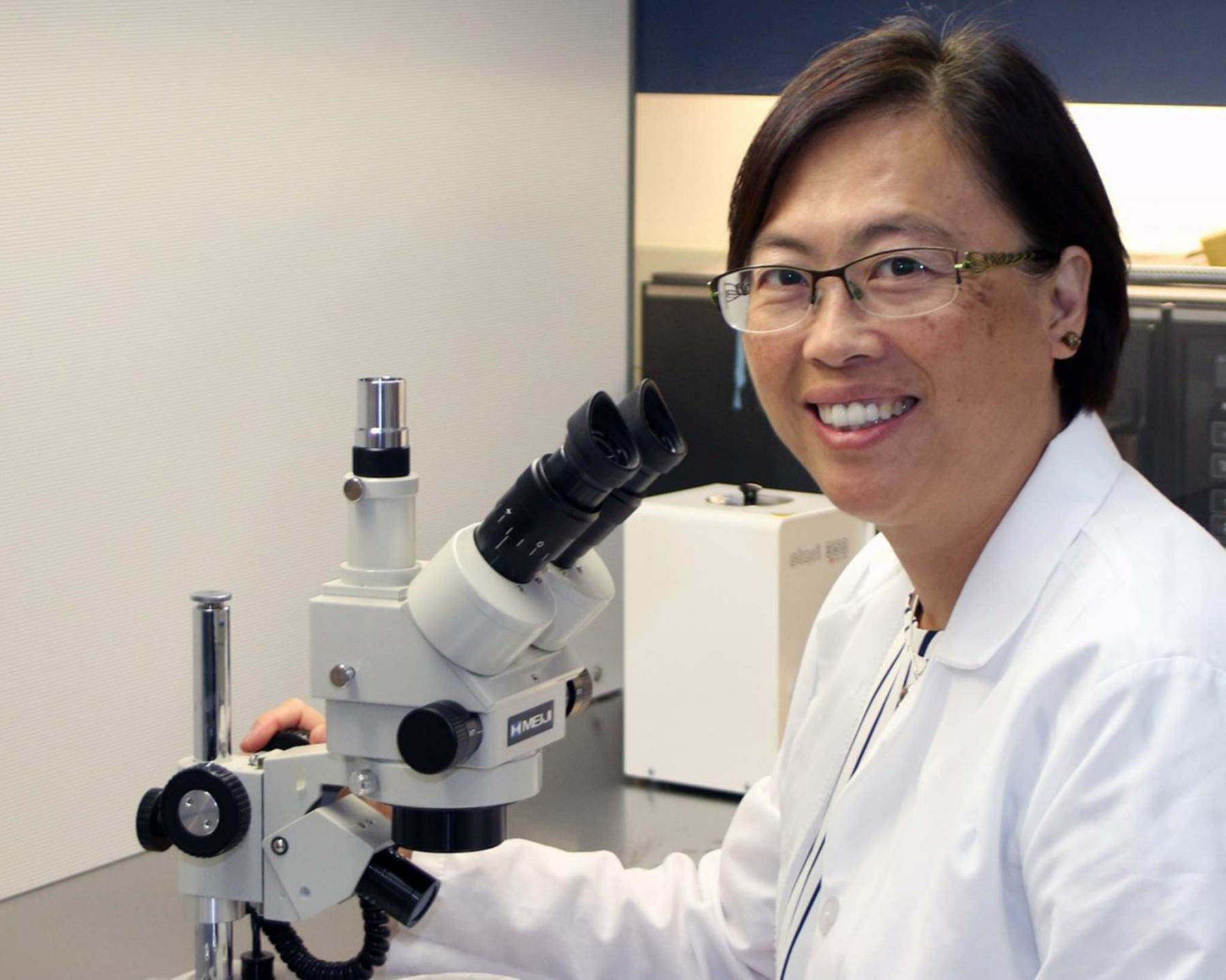

Helen Tai

Adult Colorado potato beetles feed on potato leaves.

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

Move over Yukon Gold potato and hello, AAC Canada Gold-Dorée, the new, improved and tastier kid on the block.

Imagine what a game-changer it would be to grow potato varieties that were resistant to the intense feeding and disastrous defoliation by the Colorado potato beetle. For commercial growers, the economic cost of minimizing the damage to potato crops with the use of pesticides is enormous. Home gardeners and organic growers must often employ numerous labour-intensive control methods such as picking and squishing to protect their crops from beetle damage.

Dr. Helen Tai is a breeding researcher and geneticist at the Fredericton Research and Development Centre in New Brunswick. Her groundbreaking research has led to the breeding of two new potato varieties that resist beetles. (Interestingly, Tai, whose father was a potato breeder at the Fredericton Research and Development Centre, also makes Colorado potato beetle jewellery including earrings. "The beetles are an abundant source of material for my jewellery," she says.)

Tai is well aware of the severity of the Colorado potato beetle infestation in Manitoba which is home to the second largest potato industry in Canada. The Colorado potato beetle is a major pest in Canada and causes significant damage to Canada’s $1-billion potato crop. The beetle is such an extremely dynamic feeder, says Tai, that it can adapt very quickly to most control measures including pesticides. Ever more powerful pesticides are used by commercial producers to control beetle populations until they stop working as the beetles develop a resistance.

"Potatoes are such a great crop for Canada," says Tai. "Potatoes have very good climate suitability and despite the potato beetle and other challenges such as disease, it’s relatively easy to grow potatoes compared to other crops that require warmer climates."

Tai, whose research centres around understanding the Colorado potato beetle’s adaptability and pesticide resistance, says the beetle-resistant potato varieties that she and her team have developed would be especially compatible with home gardeners and market gardeners who don’t want to use pesticides.

Potato cultivation began more than 8,000 years ago in South America. When Tai first visited South America to study the wild relatives of our domesticated potato, she was amazed and impressed by the diverse flavours, colours and shapes of the different species.

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s route to uncovering the enormous genetic diversity found in these species, as well as their potential use for breeding new and better traits into our commercial varieties, began several years ago with the collection of 200 wild potato relatives from all over the world. The wild varieties were planted by AAFC into fields with large beetle populations. The crops were not treated with any pesticides. While some of the wild varieties were defoliated, others such as Solanum brevicaule, a wild potato species that is native to parts of South America, showed only low levels of Colorado potato beetle defoliation.

Solanum brevicaule was then crossbred with domesticated potato varieties by David De Koeyer, AAFC breeder, and Yvan Pelletier, entomologist, to introduce Colorado potato beetle resistance. When Tai was hired by AAFC, she began studying seven different wild potato species and examining the molecular and chemical processes within their leaves that deter the beetle. Using advanced tools, Tai, together with her research team, succeeded in identifying the pest-repelling genes in the leaves of the wild relatives and breeding two new varieties of potatoes.

"One of the challenges that we face as breeders," says Tai, "is to get our new varieties to a wider audience or a wider set of growers." Adoption of improved vegetable varieties in Canada depends on several factors. Somebody — a company or an enterprising individual — needs to license the new variety before it can be propagated, grown, certified, and distributed. There have been expressions of interest — including from Oregon and Idaho — and trialling is well underway by some interested organic growers but as yet no one has picked up the baton and licensed the new varieties.

The two new potato varieties Tai has developed are not completely resistant to defoliation by the potato beetle. "We have seen a reduction in beetle feeding that is around 50 to 80 percent," she says.

Could the resistance be overcome by the potato beetle? "As breeders, one of the challenges we face is that the beetle is an extremely dynamic feeder and a concern we always have is that the resistance can be overcome by the beetle," says Tai. " It keeps us in business because we are always trying to develop several different lines of resistance."

It’s essential, says Tai, that growers including home gardeners utilize integrated pest management (IPM) strategies to control the amount of feeding by potato beetles. A warming climate makes IPM especially important because, as the climate changes, the beetle’s behaviour changes. "In New Brunswick and in Manitoba, we are seeing more than one generation of beetles emerging in a growing season to feed on potatoes," says Tai.

Planting your potatoes in the same location from one year to the next increases your chances for a severe beetle infestation. Crop rotation is essential. Some growers go to great lengths to control this major pest. Tai knows of one potato grower who uses a hand-held flamethrower, applying heat to the undersides of potato leaves when he spots the beetle larvae. And I thought sucking up the pests with a leaf blower or handheld car vacuum cleaner was an innovative control option.

But vacuums, flamethrowers a d propane torches aside, Tai says there are effective control options that would be suitable for home gardeners or community gardens. "At AAFC’s research farm, we dig a trench around the smaller trial plots and line the trench with plastic," she says. "Most of the beetles are walkers and once they are inside the trench, they can’t make it out."

Since potatoes do not depend on pollination to produce their underground tubers, row covers can be effective physical barriers to prevent Colorado potato beetles from accessing potato plants and laying their eggs. Growing your potatoes in planters, specially designed grow bags or polypropylene potato planters can also be effective so long as clean, new soil is used for every new crop.

In other potato news, AAFC has developed a new yellow-fleshed potato for the fresh potato market. The new variety has a unique round shape and shiny golden skin colour and is set to knock the classic Yukon Gold potato off its pedestal. Licensed in 2017 by New Brunswick-based Canadian Eastern Growers Inc. and named AAC Canada Gold-Dorée in honour of Canada 150, this new potato variety’s many attributes (in addition to its attractive good looks) include better texture and flavour, higher yield, and improved disease resistance.

The development of AAC Canada Gold-Dorée began in 2008 when the original cross was made by Agnes Murphy, AAFC research scientist. When field evaluations of the new selection began, Manitoba was one of the test locations.

AAC Canada Gold-Dorée is currently available at Metro Supermarkets in Quebec and Ontario. It will be available in other parts of the country in 2021.

colleenizacharias@gmail.com