Walter Siegmund

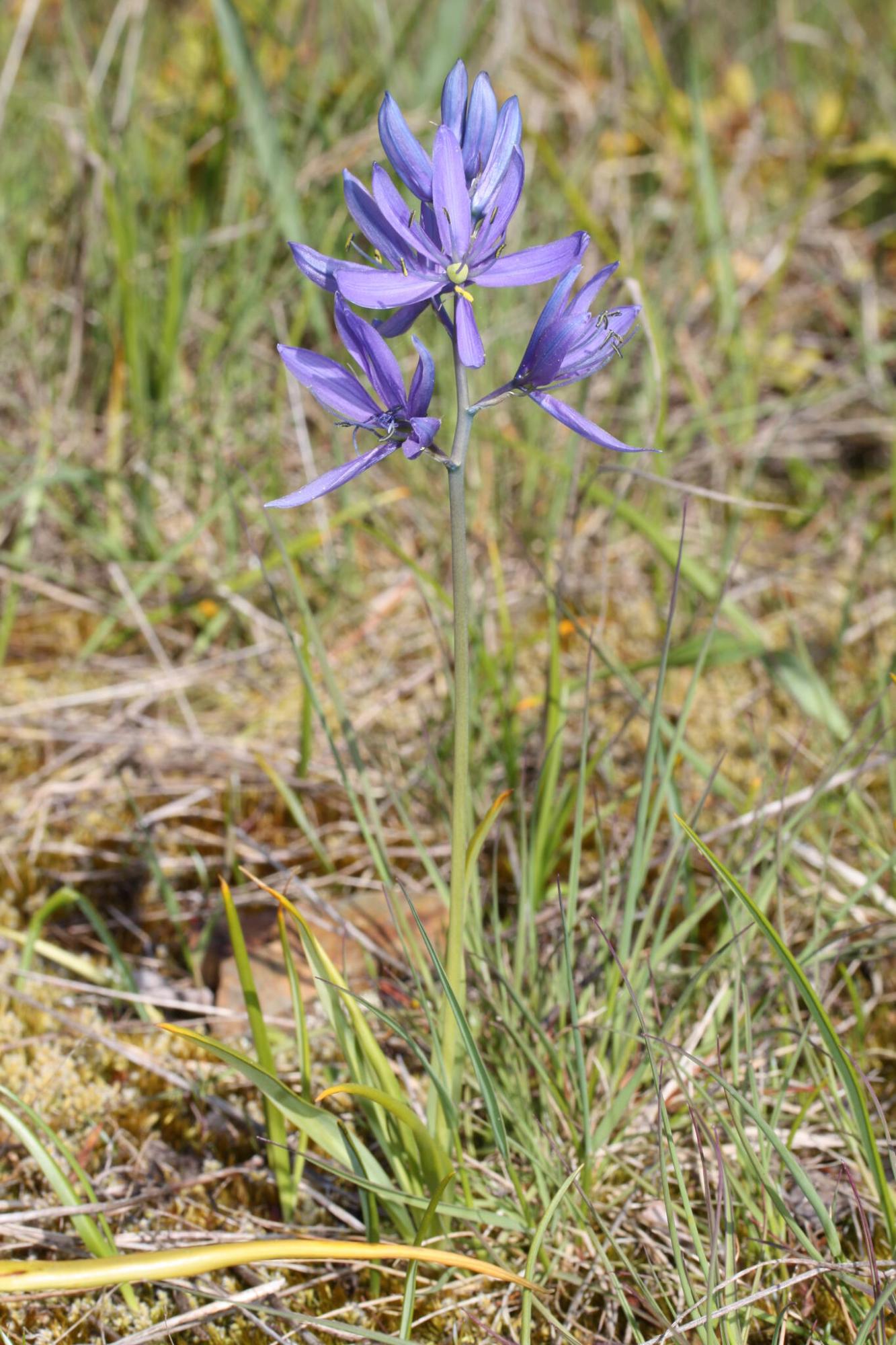

It is hoped that some of the 5,000 Camassia quamash bulbs, an important historical native plant, will establish and thrive among the prairie grasses in front of the John A. Russell Building.

Dietmar Straub

Sixty-one volunteers participated in a community planting to install 18,500 bulbs in a 500-square metres circle within an established prairie grass area.

Dietmar Straub

The tuLIPstick, an ergonomic planting tool, was developed and manufactured in-house by the faculty of architecture’s Workshop.

Photos by Colleen Zacharias / Winnipeg Free Press

Dietmar Straub and Anna Thurmayr, landscape architects and professors, invite you to visit LOTS OF BULBS, which celebrates the master of landscape architecture’s 50th Anniversary.

There’s that moment when you observe a change in a familiar setting and realize something’s happening here, but it isn’t exactly clear. So must have been the effect last fall on students, faculty, and passersby when a 500-square-metre circle was carved into the centre of an established prairie grass area in front of the John A. Russell Building at the University of Manitoba. Next, the tightly mown area was divided into 48 sections up to 12.5 square metres in size. Then, in the waning days of October, 61 volunteer students, faculty and staff of the Faculty of Architecture, along with passersby and students from other faculties, planted 300 to 500 spring flowering bulbs in each of the sections, for a total of 18,500 bulbs.

LOTS OF BULBS, as the project is called, was initiated by Dietmar Straub, a professional landscape architect and professor who teaches design studios and site planning in the environmental design program and in landscape architecture at the University of Manitoba. The project is in celebration of the 50th anniversary of the master of landscape architecture program, one of the first and most well-respected accredited landscape-architecture programs across Canada. Anna Thurmayr is the head of the department of landscape architecture. Thurmayr and Straub are partners in life as well as co-owners of Straub Thurmayr Landscape Architects and Urban Designers. They specialize in creating unique spaces that are people-and-plants-focused. Together, they see opportunity in applying spontaneity and improvisation to their projects, engaging community, stimulating discussion, and challenging people’s perceptions of nature.

The anniversary community planting will soon burst into colourful bloom and delight people and pollinators but like all Straub’s and Thurmayr’s cleverly thought through projects, there is more here than meets the eye. It is, in effect, a restoration of a restoration project. The prairie grass area in front of the Russell Building consists of 12 native plant species — green needle grass, Western wheatgrass, awned wheatgrass, nodding brome, June grass, tufted hairgrass, little bluestem, side-oats grama, blue grama grass, buffalo grass, purple prairie clover, and white prairie clover. Prior to the installation of the native grasses, the area was a storage site for construction materials. The soil was heavily compacted. The fibrous roots of grasses help to loosen soil and increase organic matter.

Straub proposed introducing new species as another step in the restoration process. “The prairie grass area was at the stage where it needed disturbance so as to sustain it for a long time,” says Thurmayr. Mowing the existing grasses, making holes to improve aeration and drainage, and incorporating other plant species was an opportunity for increasing biodiversity. It was critical, though, not to damage or disturb the roots of the prairie grasses.

“We had our own ergonomic planting tool that we dubbed the tuLIPstick,” says Straub. “A prototype was developed by Kellen Deighton, the faculty of architecture’s workshop coordinator, and it was manufactured by his team.” This sturdy tool which consists of a wooden stick with a metal tip and bracket for stepping on made it possible to pierce the heavy clay and safely create the thousands of planting holes. Once the bulbs were planted, a light mixture of lean sand and existing soil was added. The project provided hands-on experience for eager students.

“I teach my students that it is indispensable that something starts with something that’s already there,” says Straub. “For instance, with plants, we should respect what’s existing and the authorship of those who seeded it. We must identify what’s there and then we can even take advantage of what’s already there.

“I think every time when we do plantings, each case is a specific case and we always have to renegotiate the relationship between native plants and the ‘foreign’ (non-native plants) in order to facilitate our environments,” says Straub. “Those are the kind of synergies we would like to initiate between the native and non-native plants and how they can benefit from each other.” Straub is not a native plant purist. “It’s hard to design with and around dogmas,” he says. “We should stay open-minded to renegotiate over and over again. There is not just one solution,” he says.

The LOTS OF BULBS project was an opportunity to test this out, says Thurmayr, and make it public and visible. Plenty of discussion ensued in classes as to whether this was a right or wrong approach — beautiful or not beautiful — as well as among others on campus.

“Gardens are great opportunities to experiment and test new methods and plants,” says Straub. “If gardens had not already been invented, there would be such a need to invent the garden — the notion, the idea of a garden. There are so many facets to gardens, we don’t need one single definition, but you must be willing to take risks. You might have to change your aesthetic perception and with that you can change your maintenance regime and suddenly you will have something completely different — greater opportunities for increasing biodiversity compared with a highly maintained space. What is the footprint, what is the amount of energy we spend in order to get something produced? And if you want to prepare urban spaces for more biodiversity as well as for climate change, I think you have to look at those concepts.”

The bulb mixture will be present over the next three to five years before gradually disappearing. The mixture that was planted last fall included 3,500 tangerine-coloured Tulip Ballerina, 2,000 Tulip White Triumphator, 1,000 Purple Dream lily-flowered tulips, 3,500 Allium Purple Sensation, 3,500 Allium Nigrum which is a white-flowering onion also known as black garlic, and 5,000 blue-flowered Camassia quamash. It is hoped that some of the Camassia quamash, an important historical native food plant, will establish and continue to thrive among the prairie grasses. Nevertheless, even after the flowers are gone, the project is likely to stay alive in peoples’ minds, especially in the minds of people who were involved in the project, says Straub. “It’s not just about the moment, it’s actually the memory that will survive a project in the long term.” One characteristic of the projects that Thurmayr and Straub create is that most don’t have an eternal life. “They are built on the assumption that there is a cycle of growth and decay,” says Straub.

Monica Giesbrecht trained as a landscape architect at the University of Manitoba and today is a principal with HTFC Planning Design in Winnipeg. Giesbrecht says that Thurmayr and Straub, who came from Germany to teach at the U of M over a decade ago, are an invigorating addition to Winnipeg’s landscape architecture community. “They are shaping young minds into the landscape architects and urban designers of the future,” says Giesbrecht. “Landscape architects touch and impact every public space and have a huge hand in shaping urban streets and plazas. We have big-picture thinking and bring all the disciplines together — horticulturalists, civil engineers, ecologists, naturalists, climate scientists, etc. We aren’t master gardeners, and we aren’t landscapers, but we are very much collaborators. We play a crucial role in applying that lens to climate change and designing landscapes that are resilient over time.”

Join in celebrating the master of landscape architecture’s 50th anniversary by visiting LOTS OF BULBS. It’s blooming now until late spring.

colleenizacharias@gmail.com