When you walk by 139 Garfield Street, it looks like any other two-storey home on the street.

That's exactly what Deborah Stienstra and her late husband, Patrick Kellerman, had in mind when they turned a bungalow -- built in 1923 -- into a two-storey home in 1996.

The reason for the conversion was simple, says Steinstra.

"We built the second storey for more space -- for our two kids, and for Patrick, who had multiple sclerosis," she says. "Just having the one floor was confining for Patrick, so we worked with an architect to design a home that he could negotiate first with his scooter, manual wheelchair and finally a power wheelchair. To look at it from the outside, you wouldn't know the home was designed for to be fully mobility-accessible."

Inside, it's a very different story. To make the home accessible on all levels for Patrick, an elevator was installed to run through the home's centre. Having it situated that way allowed it to run from the master bedroom to the living room, and on down to the basement, where a pair of laundry ramps were placed to provide Patrick with access to the washer and dryer so he could do his own laundry without missing a beat.

"The place was completely gutted during the renovations," recalls Stienstra. "The first thing we did was the kitchen, the outside ramp, and the main floor washroom. We really had to think creatively, because we wanted to configure the home so Patrick could live as ordinary a life as possible."

Installing the elevator was just the first part of the puzzle. The next piece consisted of widening aisleways and doorways to allow Patrick easy access to the kitchen and main floor washroom. Additionally, the main floor washroom -- which has a four-foot-wide doorway -- was also enlarged (as was the one on the second floor) so that a wheelchair could manoeuvre without difficulty.

To maintain a sense of character and on the main floor -- just because a home is retrofitted to become universally accessible doesn't mean it is devoid of style -- the original hardwoods floors were retained in the living room, which also features a pair of stained glass windows, and a room next to the kitchen was turned neatly into a good-sized dining room. To add warmth, dark maple hardwoods were installed in the dining room and kitchen, and an abundance of knotty pine cabinets were placed around the kitchen's periphery.

"From the start, our goal was to design a home that was accessible, had no wasted space and was bright," she says. "With that in mind, all the hallways are wide, with short hallways to maximize space. All the rooms also have large windows to let in lots of light."

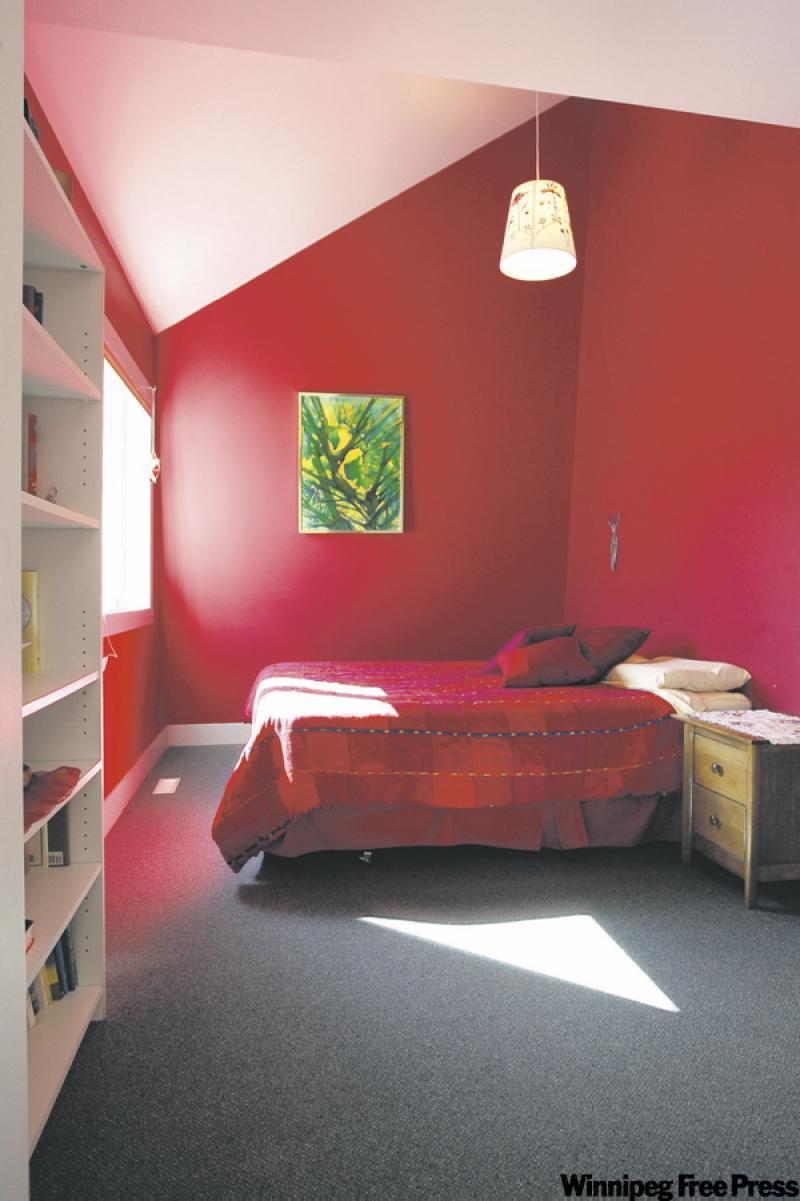

Upstairs is where the home really shines. Access comes via an angled staircase that takes you to a catwalk bordered by a modern-style oak bannister and railing. The ceiling throughout the upper level is vaulted, which simultaneously increases the feeling of space while allowing the light that spills in from the large windows to bathe each room in light.

The only features that give away the fact that it's a fully mobility-accessible home are the wide hallways, low light switches and high plug outlets.

The master bedroom (with the elevator, its own balcony and tons of room) is at the front, while the home's third bedroom is found at the back, complete with dramatic vaulted ceiling and study area with huge window overlooking the backyard. The colour palette is vibrant, yet tasteful.

"The upper level is open yet private," Stienstra says. "Even though it's been designed to be fully mobility accessible, it's still an ordinary family home that everyone can enjoy."

Chris Krawchenko, Stienstra's realtor, agrees.

"I've never come across a home like this before -- it really is a regular family home despite all the modifications, and that's what Deborah and Patrick wanted."

Stienstra, who is planning to take a sabbatical from her professorial duties at the University of Manitoba this summer, says now is the right time to let go of the home she and Patrick -- who passed away five years ago from his MS at the age of 45 -- took so much care in designing.

"It's important to me that someone else with mobility issues can get it so they can enjoy the freedom it brings," she says. "Disability is just part of life. The goal should be to live life as richly as possible despite all the challenges disability can present. Patrick wasn't disabled in our home. He could get everywhere he needed to go do to do the things he enjoyed doing. This home allowed him to live a life without barriers -- an ordinary life."